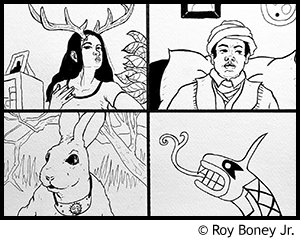

Roy Boney Jr. (Cherokee Nation), “Zoom Meeting,” 2020, pen and ink on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Now that 2020 is safely behind us, we can reflect back on the year that was defined by a global pandemic, devastating fires and storms, and racial tensions. Amid all of the sorrow and challenges, however, Native artists and arts organizations met the challenges of the year head-on, giving us several shining moments to celebrate as we look back.

1. Virtual Pivot

As the gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic hit in mid-March, and art event after event was canceled and museums and galleries shuttered, artists and organizations quickly developed new means of connecting online. Racing Magpie in Rapid City hosted virtual artist residencies. The Poeh Cultural Center hosted online classes, talking circles, and created a Virtual Art Marketplace. SWAIA, the nonprofit responsible for the annual Santa Fe Indian Market, created an online world in which people chose avatars and mingled in a virtual Indian market. Museums hosted webinars and online classes. Galleries created virtual exhibitions. Conferences went online. Many artists built their first websites or simply used social media to reach the public. We became addicted to art raffles that any artist with a online platform could host. We could easily join conferences and artist talks across the globe. While we certainly missed the physical proximity, the virtual realm leveled the playing field in terms of access. An individual artist hosting an online workshop or studio visit could be on nearly equal footing as the most prestigious museum. Stay-at-home orders forced the Native art world to do what we do best: adapt and create something new.

Screenshot from NDN World, a virtual environment on Vircadia 3D, hosted by SWAIA’s Virtual Indian Market. Image courtesy of Michelle J. Lanteri.

2. Indigenous artists of the Americas at Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN

Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unangax̂), “Shadow on the Land,” 2020, excavation and bush burial, Cockatoo Island, New South Wales, Australia. Image courtesy of the artist.

The 22nd Biennale of Sydney was the first to be organized by an Indigenous artist and curator Brook Andrew (Wiradjuri/Ngunnawal). The name NIRIN means “edge” in the Wiradjuri language of his mother, and Andrew framed the fair on seven Wiradjuri themes: Muriguwal Giiland (different stories), Bila (river, i.e. environment), Gurray (transformation), Ngawal-Guyungan (powerful ideas, i.e. the power of objects), Dhaagun (earth, i.e. sovereignty and working together), Yirawy-Dhuray (yam-connection, i.e. food) and Bagaray-Bang (healing). For those of us who could not attend in person, the biennale created copious online content, including a partnership with Google Arts & Culture, providing virtual gallery tours, explorations of the seven fair themes, and looks at individual artworks. Andrew acknowledges the colonial foundations of art biennials and says, “The very DNA of this history needs to be challenged—to be broken apart” and rebuilt on a new, inclusive model, as NIRIN exemplifies.

The stellar lineup of 108 artists and arts organizations drew heavily from Indigenous communities, especially from Aboriginal peoples of Australia, features Indigenous artists of the Americas, including Denilson Baniwa (Baniwa), Colectivo Ayllu (Mestiza/o), Demian DinéYazhi´ and R.I.S.E. (Navajo), Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/ Unangax̂), Teresa Margolles (Mestiza), Jota Mombaça (Mestizo), Elicura Chihuailaf Nahuelpán (Mapuche), Paulo Nazareth (Mestizo), Taqralik Partridge (Inuk), Adrian Stimson (Siksika), and Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers (Kainai).

3. Véxoa: We Know, São Paulo

The first contemporary Indigenous art exhibition at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Véxoa features 23 Indigenous artists and art collectives from across Brazil. Founded in 1905, this state-run museum collected its first works by contemporary Indigenous artists in 2019. These artworks created by Denilson Baniwa (Baniwa) and Jaider Esbell (Macuxi) are showcased along with historical works, customary ceremonial regalia, and recent works in paint, clay, video, and more by established and emerging artists.

Véxoa is the Terena word meaning “we know,” and curator Naine Terena, PhD (Terena), based this exhibition on Indigenous knowledge. Instead of organizing the three galleries by region, language, or time period, she adopted an Indigenous cosmological approach. Terena worked with OPY, a collaborative project by the museum, Casa do Povo cultural center, and Tekoa Kalipety, a Guarani-Mbyá community to the south of São Paulo.

Amplifying Indigenous Brazilian voices is crucial now during times of crisis, the assault on Indigenous land rights by the Bolsonaro regime, the fires in the Amazon, and the COVID-19 crisis that has been devastating to Brazil’s Indigenous communities. In fact, while Denilson Baniwa planted Nothing Gold Can Stand 1: Thread, an installation garden of medicinal plants on the museum’s grounds, he discovered he was positive for the disease. Baniwa also created an installation from the charred remains of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro that was devastated by fire in 2018— along with Indigenous artifacts and language archives of incalculable value. Activism, Indigenous autonomy, land loss, environmental degradation, theft and sale of Indigenous intellectual property, and resilience were key themes throughout the exhibition. This compelling and provocative exhibition, launched on October 31, 2020, continues through March 22, 2021.

4. BACA 2020: Kahwatsiretátie : Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie / Honouring Kinship, Montreal

With an opening date in April, the fifth edition of the Contemporary Native Art Biennial / Biennale d’art contemporain autochtone (BACA), Kahwatsiretátie : Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie / Honouring Kinship had to ride the ever-changing wave of the pandemic. Organizers successfully adapted to the quickly changing situation and provided online experiences when the pandemic rendered in-person ones impossible. David Garneau (Métis) curated Kahwatsiretátie : Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie / Honouring Kinship, with the assistance of rudi aker (Wolastoqiyik) and Faye Mullen (Anishinaabe) with 44 artists in the biennial proper and 10 in the Weaving Cultural Identities project that paired textile artists with graphic designers of diverse cultural backgrounds. The physical locations of this complex interweaving of exhibitions and experiences were Art Mûr, La Guilde, Pierre-François Ouellette arte comtemporain, and Stewart Hall Art Gallery, all in Quebec, on unceded Kanien’kehá:ka Mohawk territory, a fact that helped shape the art fair based building community relationships.

5. Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Phoenix

This year has taught us to not take anything for granted. Every March the Heard Museum Guild organizes the Indian Fair and Market on the Heard Museum grounds. Featuring more than 600 Indigenous artists, the Heard is the second-largest Native art market in the United States and the perfect break from a long winter.

This was the last time many Native artists in the United States were able to mingle in person. During the annual award showcase, we got to reconnect while checking out stellar artworks, such as the Best of Show winner, Common Ground: Culture Isn’t Black and White, a beaded cradleboard by Jamie Okuma (Luiseño/Shoshone-Bannock). The scent of citrus, children rolling down grassy green hills, watching art demonstrations on the courtyard, peals of laughter from across the booths, and the viewing, buying, and trading of artworks made by Native artists from surrounding tribes to those that flew in from Alaska, Canada, and the East Coast seems even more special now.

Rosie Yellowhair (Navajo) demonstrating sand painting at the Heard Fair, Phoenix, 2020. Photo: FAAM.

6. National Native American Veterans Memorial, Washington, DC

Officially opened on Veteran’s Day, November 11, 2020, the National Native American Veterans Memorial is the first national public monument exclusively dedicated to American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian veterans, who, incidentally, serve in the military at the highest per-capita rates of any population within the country. A decade in the planning, the memorial stands on the grounds of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian on the US National Mall. A 12-foot high, stainless-steel circle and a 20-inch high incised stone drum with an eternal flame provide a space for gatherings, ceremonies, and reflection. Visitors can attach prayer ties on the four steel lances with bronze points and feathers. Titled Warrior’s Circle of Honor, the monumental sculpture was designed by Oklahoma artist Harvey Pratt (Southern Cheyenne/Arapaho). Pratt, who served as a US Marine during the Vietnam War, is an artist and Cheyenne Peace Chief.

7. Indigenous inclusion in Vento (Wind), Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, São Paulo

The pandemic forced the São Paulo Biennial to postpone until 2021, but the foundation organized an advance physical exhibition, Vento (Wind), in the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, the biennial foundation’s headquarters in Ibirapuera Park. Named for Joan Jonas’s 1968 art film, “the exhibition composed mostly of dematerialized works, in audio and video, seeks to highlight a sense of space and distance that can rarely be experienced by the public,” as the foundation’s website explains. Curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti and Paulo Miyada, the ethereal exhibition included an impressive array of Indigenous artists of the Americas including Gustavo Caboco (Wapishana), Jaider Esbell (Macuxi), Paulo Nazareth (Mestizo), Uýra Sodoma (Munduruku), Sebastián Calfuqueo Aliste (Mapuche), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish/Cree/Shoshone), and Abel Rodríguez (Nonuya). This reflects a growing movement to integrate Indigenous arts into the Brazilian contemporary art canon. The planned art fair will build upon themes introduce in Vento.

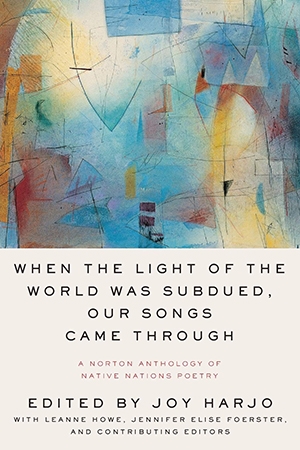

8.When the Light of the World Was Subdued Our Songs Came Through

W. W. Norton & Company released this anthology of Native American poetry right when we needed it most. Edited by Joy Harjo (Muscogee), LeAnne Howe (Choctaw Nation), Jennifer Elise Foerster (Muscogee), this collection of poetry offers an expansive sweep of powerful writing from Indigenous voices. Harjo was just named US Poet Laureate, the first Indigenous person to ever hold this position, for an unprecedented third successive term. Pulitzer Prize–winner N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) leads the writing with a blessing. The 400 pages span 300 years of poetry. Though it begins with a poem first composed in Latin by Harvard University student Eleazor (Wampanoag) in 1678, the three editors organized the remaining poems not chronologically but geographically, celebrating place-based knowledge and the poets’ connection to their homelands. In all, 161 authors from 90 Native nations contributed to this expansive collection that Oprah Winfrey selected as one of her seven “Books That Help her Through Tough Times.”

9. The Lighting of the Teepees: A Symbol of Hope, Billings

Seven tipis with pink prayer ties streaming from their crowns appeared in a line atop the sandstone Rimrocks at Swords Park in Billings, Montana this December. The lodges are highly visible, and at night they glow with brilliant colors over the skyline. Crow tribal members erected the tipis to commemorate those who have walked on after contracting COVID-19, honor those who have cancer, and to give hope to the local community.

Not only portable housing, tipis are also metaphors. To the Apsáalooke, Crow people, each tipi pole holds symbolism of seasons, directions, significant animals, and more. The canvas that covers each structure represents the protection of the family that would inhabit each.

More than 20 volunteers helped with the installation, including tribal member William Snell and his son Jade. Funded by the Harry L. Willett Foundation, the Crow Tribe of Montana worked with the Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council, Sky Wind World, Inc., and the Pretty Shield Foundation, which owns the tipis, for this project.

Visitors were encouraged to write names of departed loved ones on the tipi canvases and to leave rocks around the perimeters of the lodge in commemoration. These stone tipi rings, which will remain long after the tipis have been taken down, are reminiscent of those stone circles that have marked preferred campsites throughout the Northern Plains for millennia.

“The Lighting of the Teepees: A Symbol of Hope” at night. Flight into Billings Logan International Airport visible through long exposure. Photo: Mike Clark. Image courtesy of Mike Clark and the Billings Gazette. Used with permission.

10. STTLMNT

The Consciousness Sisters CIC, a Plymouth-based interdisciplinary duo, reached out to Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara/Lakota) about creating an Indigenous-led component to Mayflower 400, a program of events commemorating the 1620 voyage of the Mayflower ship, filled with Pilgrim colonists, that traveled from England to Cape Cod in Wampanoag territory. A month-long encampment in the Central Park of Plymouth, England, Settlement was planned. However, with the onset of COVID, the artists made a radical shift to create STTLMNT, a year-long “Indigenous Digital Occupation.” STTLMNT partnered with organizations such as A Blade of Green, NDN Collective, and the Tulsa Artist Fellowship and used consensus, as opposed to curation, in its decision-making process. Thirty-three artists, Indigenous and of Indigenous descent, created digital artworks, performances, conversations, videos, and interventions that are still in the process of unfolding.